Blood Chits and Marine Aircrews in Combat

Blood Chits carried by Marine aircrews in combat

Blood Chit is the common term for the written notice, in several languages, carried by Marine aircrews in combat. If their aircraft is shot down, the notice (1) identifies the Americans and (2) encourages the local population to assist them.

The concept is over 200 years old. Jean-Pierre Blanchard, the famous French balloonist, came to America in 1793 to demonstrate hot air balloon flight. He would ascend from Philadelphia. Where he would come down, of course, no one knew. And, Blanchard did not speak English. George Washington, U.S. President, gave Blanchard a letter addressed to “All citizens of the United States.” The letter asked that Blanchard be befriended and given safe passage back to Philadelphia.

This idea lay dormant for over 100 years. But, in World War I the British RAF issued “ransom notes” to its pilots flying in India and Mesopotamia. These notes, written in Arabic, Urdu, Farsi, and Pashto, promised a reward to anyone bringing an unharmed British pilot or observer to the nearest British outpost. British airmen called the notes goolie chits. (Goolie was the Hindustani word for ball, and many hostile tribesmen had been turning captured airmen over to local women for castration.)

When the mercenary Flying Tigers went to China in 1937 to battle the Japanese, they carried blood chits. These printed notices bore the Chinese flag and Chinese lettering which stated:

This foreign person has come to China to help in the war effort. Soldiers and civilians, one and all, should rescue, protect, and provide him with medical care.

Later, when the United States entered the war in 1941, it issued blood chits in almost 50 different languages. And, a reward was offered to those who assisted downed fliers.

The U.S. government kept its word. The greatest reward ever given went to the family that aided a B-29 crew shot down on 12 July 1950, two weeks after the start of the Korean War. The crewmen, badly injured, were found by North Korean civilians. Yu Ho Chun found the blood chit in the pocket of one flier. He gave the Americans medical aid. Then, at great personal risk, he put them on a junk and sailed them 100 miles down the coast to safety. Two weeks later the North Korean Army found Chun, tortured him, and then killed him. But, 43 years later in 1993 the United States paid $100,000.00 to his son, Yu Song Dan.

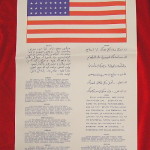

During the war in Vietnam the fighter, attack, and helicopter crews carried new blood chits. These chits displayed the American flag, plus an appeal in 14 languages: English, Burmese, Thai, Old Chinese, New Chinese, Laotian, Cambodian, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Visayan, Malayan, French, Indonesian, and Dutch. The wording in each language was the same:

What did the Blood Chits carried by helicopter crews in Vietnam say?

I am a citizen of the United States of America. I do not speak your language. Misfortune forces me to seek your assistance in obtaining food, shelter, and protection. Please take me to someone who will provide for my safety and see that I am returned to my people. My government will reward you.

In Vietnam, as in World War II, some unique missions required unique measures. On certain Black Ops flights, in addition to their blood chits, the aircrews carried paper money and gold coins. Needless to say, these required strict inventory control. Upon return from a mission, “I just lost it!” wouldn’t work.

Today the United States has pre-printed blood chits most for locations throughout the world. Blood chits, in the appropriate languages, were issued to airmen for operations in Panama, Grenada, Somalia, Bosnia, and the Gulf War. Since the Gulf War, use of blood chits has continued among airmen flying the hostile skies of Southwest Asia. Today the blood chit package includes money, and sometimes a pointee-talkee pictorial display.

This should answer the questions:

What is a blood chit?

Who would carry a blood chit?

When did american aviators first start carrying blood chits?